Who is who? Whose mind am I in? Is this reality or one character’s fantasy?

Persona blurred the lines between reality and dream, while also somehow making it excruciatingly clear what was which with the use of visuals and music that merited particularly dreamlike sequences, and the silence that accompanied real life interactions. However, once you think you understand and know what you are seeing, the film shifts once more, such as when at the end we see a camera crew filming the character of Alma, and we are once again left to ponder reality.

Before going into the intricacies of the film’s story, the film in itself is a work of art – a disturbing one, to say the least. The very first sequence of black and white scenes showed scenes that begged its viewers to be uncomfortable – the nailing of the hand, the lamb slaughter, and the close up images of photographs and videos in history Elisabeth examines later on in the film. In hindsight, the scenes that left me most uncomfortable were perhaps the ones shared between the two characters.

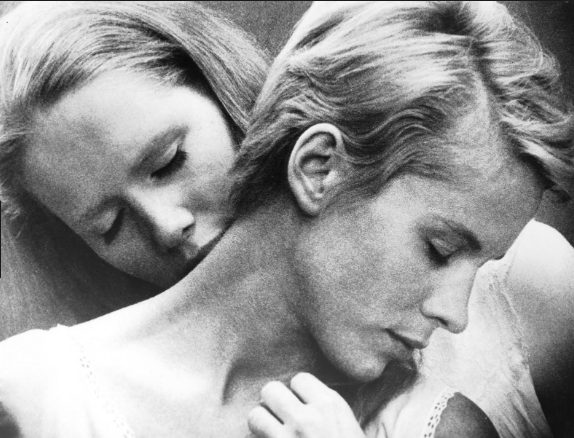

A paradox I experienced while watching was that, initially, I believe this film is multiply diagetic – many times it reminded me that what I was watching was a film, and I was merely a viewer. And yet all throughout the film I felt discomfort at the intimacy I was experiencing with the characters – many times I felt I was intruding, that I was so connected to these two characters, real characters, living real moments of intimacy that I shouldn’t be watching. Perhaps this was due to the exceedingly close up visuals the two characters, the consistent lack of space shared between them, the scene wherein Alma watched and smelled Elisabeth in her sleep. Furthermore, all throughout the film, as the two women seemingly merged into one, this is made clearer to us both through imagery and the narrative.

Story-wise, as Elisabeth remains quiet and Alma speaks at length about her life, we may come to the conclusion that the premise of the story seems to seek to imply that as the two women spend more and more time together – one in silence and one in awe and admiration of the other – the lines between the two women blur. More tangentially, that Elisabet is a representation of the persona we portray to others at first sight in our apparate unknowability, while Alma represents the chaos and range of stories and emotions that actually comprise our person – throughout the entirety of the film, Alma portrays a range of emotions – some straightforward, such as anger, frustration, drunken joy, guilt at her abortion. Other times, she reflects a multiplicity of conflicting emotions (re: the climactic scene at the end wherein she is chasing after Elisabet and alternates between cursing her and crying on the ground.

However, this insight is made only clearer through the use of visuals in the story – the picture of the two women merged as one, the entirety of the scene with Elisabet’s husband, the scenes of the two women when Elisabet places her hand on Alma’s forehead and they look towards the side. Persona asks more questions than it answers, and the beauty of the film is the multiplicity of ways we can interpret it depending on who we are and where we are in our lives. Is this a story that shows two women merging into one? A story that highlights how strikingly similar they already were to begin with, bonding over the guilt of postpartum depression? A story of the chasm between who you are to others and to yourself? Or is it about none of those, and rather a simple story about an actress who refuses to talk, her nurse, living in a house together for a time, interacting and spending time with each other, before going their separate ways? Are the assumptions of merging and other things we may draw only a figment of our overactive imaginations based on how their simple story is portrayed on-screen? What astounded me in Persona was that it made me realise how cinema has the capacity to make simple stories come alive – to make us feel things such as fear, a sense of eeriness, a sense of discomfort; to make us draw conclusions about life and reality and the characters and their story, simply from how their story is portrayed and plotted – the visuals, the music, etc.

The lack of proper closure at the end of the film when the two women part, though feeling like a betrayal, could also be interpreted in in a variety of ways – it could be a reflection of our reality in that in real life, closure is not always guaranteed, and some things merely end as is. It could be a testament to Art Cinema and its rebellion against Hollywood’s desire for a proper ending. The latter would be further justified by the scene showing the cameramen at the end, as it further shatters our immersion in the story. But then again, it could be an artistic display pertaining to the idea of how, as Alma leaves the set, she is no longer connected to Elisabet, the woman she was becoming, the woman represented her and all Personas. I left the film with more questions than answers, feeling a multiplicity of emotions I hadn’t felt prior to viewing – merely by watching two women spending time with one another. Simply talking, simply living.