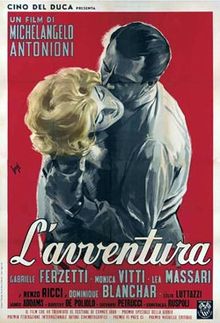

In Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura, I was really immersed in what most would say represents the stereotypical European art film. My first impression is that it really tests the audience patience in being fully engaged in the movie. The film is very long and not much really happens the whole time. So for a regular movie watcher, this film would be a difficult watch because it is opposite from the typical Hollywood tropes that happen in mainstream films. It sometimes feels like a chore to watch because of the lack of intense action that happen in the long duration of the movie. But, with all the more subdued instances in the film, you can appreciate the little details that further make this an art film.

It really shows how diverse the European art films from each country, especially compared to the Godard and Bergman movies. This movie really savours in its slow burn mystery turned romance movie. Like many of the art films that has been made throughout the years, the film also showed peculiarity in its depiction of the characters. One noteworthy aspect of the film was how only Claudia seemed to be worried about Anna in the duration of the film. The weird scene with Claudia, Guilia and the painter, further highlights the indifference of almost all the characters in what would normally be a major issue. The characters feel like they were in another world and that they don’t act normally like how people outside of the film act. There is also a bourgeois attitude among the characters and they are normally either in lavish parties or in vacation. This really makes the typical audience to feel disconnected with the people they are watching on screen. None of them really feel relatable and I felt that this was intentional so that it is emphasized even further the alienation of Claudia from the world she is in after the sudden disappearance of Anna.

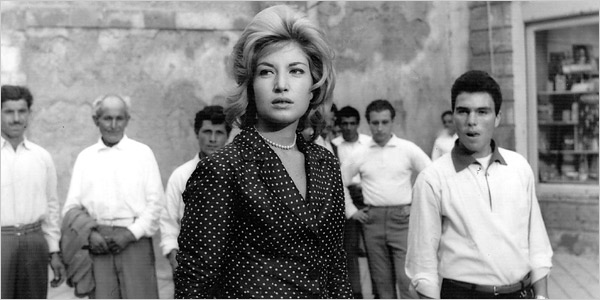

Monica Vitti is also very engaging in her role as Claudia as she oozes a very chic vibe from the moment she steps on screen. She also embodies this alienation very well because her evolution throughout the film is quite evident. From being this laid back person to the hysterical attitude she became by the end of the film. The film really relies on her because she is the heart of the movie and she really demonstrates her acting range in the movie.

But, the strongest part of the film is evidently the visual aspect. The film, like most art films, really looks beautiful in every frame. The images are all striking and fully enhanced by having attractive looking actors to be in them. The cinematography of the movie is its greatest asset because rather than telling you what’s happening it shows you with the beautifully shot images. But, for me the most striking aspect were the costumes worn by the actors, specifically Monica Vitti’s Claudia. Here clothes are very cool and chic and was able to represent high fashion that could have easily walked the runways of Paris and Milan.

Enrico R. Barruela COM 115.5 A

Looking at merely the first arc of the film—from the introduction of the characters, the wealthy upbringing, the passion shared by the characters, to the unexpected and mysterious loss of the seemingly primed major character Anna—it was beginning to look like any other film, since creating a conflict which would presumably be the center of the story. It is not the case in L’Avventura, however. The film is not about the search for a mysteriously missing woman. It is about the adventure.

Looking at merely the first arc of the film—from the introduction of the characters, the wealthy upbringing, the passion shared by the characters, to the unexpected and mysterious loss of the seemingly primed major character Anna—it was beginning to look like any other film, since creating a conflict which would presumably be the center of the story. It is not the case in L’Avventura, however. The film is not about the search for a mysteriously missing woman. It is about the adventure.